GOVERNOR GRINCH?

Ted Strickland annoys state employees with a new order: Do charity work on your time, not the taxpayers’by Erik Johns / December 20, 2007

|

|

| File | |

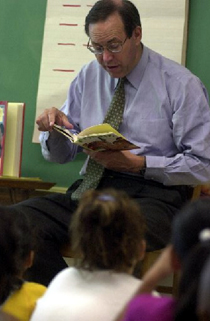

| The old days: Among the state employees who took time out of their work day for charity work was then-Gov. Bob Taft, founder of the Ohio Reads program | |

You can almost picture Charles Dickens writing this in an early draft of A Christmas Carol. Bob Cratchit, the downtrodden clerk for wealthy financier Ebenezer Scrooge, asks his grumpy boss for the afternoon off so he can help out at the local orphanage.

“Bah, humbug!”

A lot of state employees have probably muttered the same things about Gov. Ted Strickland, who has made yet another decision that impresses the people he works for while annoying the people who work for him.

The governor, in a policy directive that took effect last month, banned all state employees from participating in charitable and volunteer activities on state time.

For a lot of Ohio taxpayers, the reaction to that news might be: Employees were allowed to participate in charitable work on state time?

State employees had been able to leave the office for up to four hours every two-week pay period—without being charged for vacation—to engage in charitable deeds for former Gov. Taft’s Ohio Reads program, the Adopt-a-School tutoring program, Operation Feed and a special United Way project.

“Governor Strickland encourages State of Ohio employees to engage in charitable activities in support of worthy causes,” reads a memo explaining the new rules. “At the same time, the governor firmly believes that, while on the state clock, Ohio’s taxpayers expect state employees to do the jobs they are being paid to do. During ‘on the clock’ hours, state employees should, with very limited exception, be engaging in the work for which they’ve been hired.”

Typical in-office charity activities are still allowed: gathering canned goods, collecting money, participating in blood drives. But if you take off to, say, be a reading tutor, you’re now on your own time, not the taxpayers’.

“Governor Strickland believes that the essence of volunteerism is the donation of one’s own time to a cause,” the memo reads. “Accordingly, state employees desiring to provide substantial, ongoing, regular volunteer services to charitable entities will need to do so before or after work, during lunch, or other authorized break periods on weekends or during other non-state time.”

The old policy dates back to April 1999, Taft’s first year in office. It was amended in September of that year to allow state workers to volunteer for his Ohio Reads program. Department heads were required to keep track of the volunteer hours and provide an annual report.

Keith Dailey, the governor’s spokesman, said that policy was identified as a

problem “as part of a very natural review of current policies and

procedures.”

Dailey said under Taft, a popular time to perform charitable deeds was right before the weekend. He said he heard tales of a group of state employees that would leave the office for several hours every Friday to do volunteer work.

“The policy reflects the state’s view that while working on the state clock, state employees ought to be attending to their state duties,” he said. “It would be disappointing if people stopped volunteering or engaging in charitable activity because they can no longer do it while being paid by the state.”

“The governor’s goal was not to be punitive.”

But it clearly feels that way to some state employees. One, who asked to remain anonymous, said she often tutored children in local schools during the week. But with the new policy in effect, she no longer has the time.

“I was really disappointed,” she said. “It’s just hurting the kids.”

She said she understood that Strickland is in a belt-tightening mode but doesn’t think outside charity work is the best place to start eliminating government inefficiency.

“Well, shoot,” she said, “there’s people who work for the state that can piss away an entire day doing nothing.”

While applicable to all volunteer efforts, the policy memo mentions one specific charitable activity by name: the United Way’s annual Community Care Day.

This year, state agencies provided 312 volunteers for the Sept. 18 event, which brought together more than 5,000 people from Central Ohio to engage in a variety of charitable works on a Tuesday.

Next year, state workers who want to participate will have to take personal leave.

Kermit Whitfield, spokesman for the United Way of Central Ohio, said he hopes those people will continue to volunteer, even though they would need to do it on their own time.

“I don’t know exactly how this is going to play out for next year,” Whitfield said. “But we certainly don’t want to second guess the governor. He’s got to look at his budget and make decisions based on that.”

This isn’t the first time Strickland, who took office at the start of the year, has eliminated a perk enjoyed by state employees. In March, after learning about exorbitant meal expenditures by the Ohio Board of Regents, he put a freeze on food purchases by state agencies.

In a little less than four years, state agencies had racked up an $8.2 million food tab—including numerous trips to fancy restaurants—on the backs of Ohio taxpayers.

The food policy already has inspired grumbling by workers who have begun brown-bagging during lunch events that were once catered. This month, they’re learning how it affects their office holiday parties.

In one notable state office, the answer is: not much. Strickland’s staff enjoyed a holiday party at the Governor’s Residence, complete with an impressive spread. It was paid for from his campaign fund, not tax coffers.

Of course, cabinet-level state departments aren’t headed by politicians with campaign war chests they can dip into. Dailey said he expects special funds and pass-the-hat efforts are allowing state agencies to throw their own holiday parties.

The Ohio Consumers Council did just that, tapping into a special fund fed by employees for office activities.

But the losers weren’t just career bureaucrats deprived of a free candy cane on Friday afternoon. One state agency took a hit in attendance at a program for low-income families because there was no longer the promise of a meal to go with an information seminar.

“Our office had to do away with different events that we used to do and scale back on some things,” an employee of the agency said. “We’ve got to follow what the governor says. In the end, he controls the budget.”

Sam Gresham, vice chairman of the nonprofit watchdog group Common Cause Ohio, leads an organization that depends on volunteer support to succeed. Nonetheless, he supports Strickland’s stance.

“From an ethical standpoint, it’s a good idea,” Gresham said. “There’s no fuzziness about what you’re doing with your time.” He added, “But I hope this doesn’t reduce the amount of time state individuals give.”

Dailey said in tight financial times, it’s government’s duty to curb non-essential expenditures.

“You don’t have to have lunch meetings,” he said. “You can have meetings and break for lunch.”

Dailey emphasized that both the food and charity policies are purely the result of a sound fiscal approach.

“All state employees,” he said, “have a responsibility to be good stewards of taxpayer dollars.”